Last updated July 8, 2024

For no-tillers, the planter is the most crucial piece of equipment on their farm. It does the job of opening a slit in the soil, dropping in seed and closing the seed trench, all while managing residue efficiently in the field.

Because of this, it’s important to make sure planters are always in good working order. This means checking that planter units are tight, double disk openers have the proper diameter and contact, seed firmers are not overly worn, and row cleaners and closing wheels are in good condition.

When no-tilling began to take hold during the 1970s, planters available on the market were mostly designed for conventional farming with drier soils with far less residue on the ground, while no-tillers were dealing with more residue and higher soil moisture.

Even today, most planters don’t come from manufacturers ready for no-till practices, although some of them have been known to permit custom ordering of no-till components with new machines.

This article will take you through the basic components of a no-till planter and provide you with tips for no-till planter maintenance from experienced pros in the industry.

No-Till Row Cleaners

With tremendous pressure placed on timely planting, no-tillers are looking to have their planters functioning at a high level to maximize emergence and yields. For many no-tillers, row cleaners are the first line of attack to clear the seed zone of trash and prepare ideal planting conditions.

This is especially important if residue is moist because of increased risk of hairpinning.

But row cleaners that are incompatible for field conditions, or set improperly, can throw the planting process off at the very beginning. They can dig furrows in the soil or leave trash in the row, causing a bumpy ride for row units and interfering with seed depth and singulation.

Manufacturers have come forward with new designs for row cleaners that tackle specific challenges in the field. Some units have swept-back teeth to more aggressively handle difficult soils and sweep trash out of the way.

Some have treader wheels that sweep residue away from the surface or are “floating” models that adjust to undulations in the terrain, an asset to no-tillers farming slopes or highly variable soils.

Another new option is sophisticated systems that let no-tillers adjust the aggressiveness of row cleaners from the tractor cab when residue levels or field conditions require it.

Bill Lehmkuhl, a longtime no-tiller and owner of Precision Agri-Services in Minster, Ohio, believes row cleaners are important in most no-till situations because they smooth out the path for row units.

“Fewer bumps and jumps allow the seed meter to singulate seeds more effectively and the seed tube to direct the seed smoothly to the bottom of the trench,” Lehmkuhl says.

Moving residue out of the opener path is another essential function, Lehmkuhl says. If residue is hairpinned with the seed, it invites disease into the furrow. Disease, poor singulation and poorly placed seeds all contribute to uneven emergence.

“When the first corn plant emerges, the rest should follow within 24 to 48 hours,” Lehmkuhl says. “Uneven emergence can greatly impact yield. If a plant is one leaf collar behind its neighbor, it can have a 7-bushel-per-acre impact on yield.

“You pay the same for the seed that became a weed as the one that produced an ear, but it provides no return and can hamper the plants around it.”

What row cleaners shouldn’t do is throw a lot of dirt or be aggressive enough that they’re actually digging a trench. Lehmkuhl says it’s fine to look back and see them resting every once in awhile and to have them only engage when residue is present.

Lehmkuhl also advises no-tillers use floating row cleaners over fixed units. On his own farm, Lehmkuhl says he’s seen a 6-bushel-per-acre yield advantage with floating row cleaners over fixed.

“I’ve actually seen it happen. As you go through the field and its changing environment, you can hold that row unit up with a fixed row cleaner and you’re actually changing the depth of that row unit — you’re plowing out,” he explains. “That floating row cleaner provides more consistency as you go through the field.”

No-tillers should make sure row cleaners are clearing the residue for the gauge wheels. To do that, Lehmkuhl says to measure the width of the row unit from the outside of the gauge wheels.

“Then go to the row cleaners and look to see how far those row cleaners are moving that residue away from where the gauge wheels run,” he says.

“If you’re planting into some heavy residue, we can run into some issues if they’re not moving that residue far enough and our gauge wheels — which function as our depth control — are running right over the top of that strip of residue.”

The solution may be switching to row cleaners that have a wider stance or using narrower gauge wheels.

He also recommends using depth bands on the floating row cleaners so they don’t go in too deep.

While row cleaners can now be adjusted from the cab, it’s still no excuse to not get out and check how row units are performing in the field, Lehmkuhl adds. No-tillers should look for any hairpinning of residue, which can cause seed-borne diseases.

No-Till Closing Wheels

Closing wheels have the crucial job of closing the seed slot in tough-no-till conditions. Improper closure can hurt emergence and yield and ruin all of the other progress you’ve made getting no-tilling to work.

If closing wheels aren’t set up and adjusted properly, or if no-tillers fail to account for changing field conditions, furrows can dry out and open back up or sidewall compaction can seal too tightly and cause delays in germination or emergence.

When planting is done and crops begin to emerge, no-tillers have a chance to evaluate how well their planter has performed — including whether the row unit’s closing wheels are doing the job closing the seed slot.

Field variability, tougher residue and growers’ early-planting ambitions have also driven many improvements to closing wheels.

Most planters only offered smooth, rubber-coated wheels that required high amounts of down pressure to close the seed slot. That level of down pressure might be necessary in some soil conditions and soil types, but in wetter soils sidewall compaction became an issue. And there were many complaints about seed slots not being closed properly.

Penn State Extension recommends using spiked, rippled or posi-close closing wheels instead to avoid excessively packing the soil on top of the seed while still effectively closing the seed slot.

No-Till Farmer spoke to industry sources and experts about the pros and cons of various closing-wheel setups and what questions no-tillers should ask if they’re planning to buy or switch out closing wheels.

Closing Wheel Setup Pros And Cons

Closing seed trenches and optimizing seed-to-soil contact is essential for uniform emergence, leading to higher yields.

“This is achieved by filling the seed trench from the bottom up and firming the soil while eliminating air pockets,” says Jared Chester, agronomy and data information specialist at Beck’s. “Open slots also allow herbicides and insects, such as slugs, direct access to the seed. When planting conditions are not ideal, spiked closing wheels are essential to close the trench, eliminate sidewall compaction and prevent restricted root growth.”

Moisture comes into play when growers decide how to set up the closing wheels on their planter, or whether they go with double wheels of the same type or a combination of styles.

It’s typical to see more spading-type wheels in the eastern Corn Belt, where farms may have wetter soils and higher clay content, says Mark Hanna, an ag engineer at Iowa State University. In drier climates in the western Corn Belt, with more variable soils, he believes conventional wheels may better fit the bill.

“With spader wheels, you still have load on the surface. But it’s intermittent, point loads,” Hanna says. “This tends to give you more aggregated soil that’s looser on the top. If you’re really trying to pack the furrow pretty well, those wheels might have some limitations.”

Phil Needham, owner of Needham Technologies in Calhoun, Ky., says most growers planting into higher-moisture soils will select a pair of spiked closing wheels because smooth wheels will rarely close the slot consistently in those conditions, even with maximum down pressure.

“A pair of spiked wheels will close the seed slot, gain good seed-to-soil contact and leave loose soil above the seed,” he says.

Variability of soil conditions from one field to the next, and even within fields, is another challenge many no-tillers face. One possible way to address it is installing one spoked and one rubber closing wheel.

“A half-and-half mix is like hedging your bets,” Hanna says. “If it was my planter, I would look at the local soil situation. If it seems like 3 out of 5 years it’s always wet, then I can look at finger-style wheels. Or I can do the 50-50 setup and hedge my bets.”

Adds Needham, “Any closing system which gently spades in the sidewalls is going to accelerate emergence, allow faster lateral rooting and access to nutrients and moisture, compared to heavy downforces which press the soil together.”

Hanna says it’s hard to find research data on how different closing wheels affect crop emergence, stands and yields.

In the last 2 years on a research farm in northwest Iowa, Iowa State researchers compared results of corn crops planted with different types of closing-wheel setups — two rubber-coated wheels, two spading wheels and a combination of one each.

The farm plots included conventional tillage and no-till, and an emergence-rate index was used to assign progressively higher scores to faster-emerging corn plants.

Hanna says the emergence rate was higher at the test site in northwest Iowa where conventional, rubber-coated wheels were used. Otherwise, there weren’t any differences in emergence, stand or yields with different types of wheels. Seed-firming devices were not used during the research.

On the other hand, Chester says Beck’s 2023 Practical Farm Research (PFR) study on closing wheels has shown consistent improvements in yields for aftermarket designs that replace OEM rubber-wheel pairs.

“PFR data indicates the proper closing wheel varies depending on a farmer’s soil type and planting practices, but nearly all aftermarket wheels have performed better than the two solid rubber wheels that come standard on most planters,” he says.

Installation is the key to good success with any aftermarket wheel, Chester notes. Every closing wheel manufacturer publishes a recommended installation for proper spacing, and Chester says the Beck’s team mounts closing wheels exactly as the manufacturer recommends. From there, they can be adjusted in the field if needed.

Tips for Adjusting Closing Wheels

Having the right closing wheels for your planter isn’t enough. They can only be effective if no-tillers calibrate their planters properly for the conditions they’re facing during planting season.

“The closer you are to marginal soil conditions, the more you need to pay attention to some of those things,” Hanna says. “Particularly for no-till, that’s your one chance to get it right, so adjustments take on more significance.”

Tim Boring, Michigan State University crops and soils agronomist, says growers should take some time to dig around the seed furrow — not only just after the planter pass, but also on a few occasions early in the season, across soil types and planting conditions.

“Think about keeping a short log of the planting conditions to see how they might correlate with plant emergence and growth,” Boring says. “More than anything, be sure to keep an eye on your planter setup as conditions change. The little changes to improve seedbed conditions can have a big impact on crop performance.”

Hanna and Needham shared some tips no-tillers should consider when setting up closing wheels on their planters:

- Keep Your Distance. Needham says many growers get in a hurry and install wheels too close or too far apart. He suggests they read the instructions for their planters closely to identify the correct distance.

- Think About Alignment. Double closing wheels need to track over the furrows, but they can easily be knocked off alignment if a planter bumps an object or is jostled around in the field or in transit, Hanna says.

-

Down pressure Settings. When Hanna does workshops in the field, he polls farmers on whether they know their planter has an adjustment for closing-wheel down pressure. Most of them know that it exists.

“But if I ask them who actually changes the down pressure, the numbers drop off real fast — it’s way short of 50%,” he says.

Hanna says it’s possible to adjust closing wheels so they run in a float position, with little more than the weight of the wheels applying pressure, or higher pressure can be set to provide more seed-to-soil contact.

Too much down pressure, however, can have dire consequences. In wet soil, a combination of aggressive closing wheels and excessive down pressure could till the seed out of the furrow or worsen sidewall compaction.

Hanna suggests no-tillers worried about closing the seed slot use tines or drag chains instead of ratcheting up the down pressure. -

Level Those Arms. Another forgotten area is closing-wheel arms. If they’re not level, the performance of the wheels will suffer, Needham says. Eccentric or slotted systems available on most newer planters can be used to make the proper adjustment.

“While 13-inch spiked closing wheels are 1 inch greater in diameter than a standard smooth wheel, when they engage the soil in looser areas of the field — or when operators apply too much downforce — you’ll find that the closing-wheel arms descend too far at the back,” Needham says. ”As the rear of the closing-wheel arm lowers, the gathering action of the closing wheels is reduced.

“At a point around 10 degrees less than horizontal, it changes to a negative gathering action, which makes closing the seed slot almost impossible in difficult conditions.”

Needham also notes that if a planter drawbar is down at the tongue end, the planter closing wheel arms will be lower at the back, so growers need to begin by leveling the planter drawbar.

No-Till Gauge Wheels

Gauge wheels are another accessory on planters that no-tillers should pay close attention to.

Penn State Extension suggests that gauge wheels can be useful to avoid packing the soil too much. Some depth gauge wheels have a depression next to the double disk openers to reduce the threat of soil compaction while still properly closing the seed slot.

Gauge wheels, experts seem to agree, aren’t doted over nearly as much — even though they perform an essential function of establishing consistent seed-depth placement that is key to uniform emergence.

“I honestly can’t believe it sometimes when I go out and look at some planters and see the condition the gauge wheels are in, and that’s so important,” says Andy Thompson, an area manager for Yetter Mfg.

But as no-till practices continue to grow, and demands placed on planters continue to increase, gauge-wheel dimension designs are undergoing some important changes.

Gauge wheel designs are featuring newer, more durable materials, as well as open, spoked wheels that allow mud and residue to flow through the row unit without plugging up the wheels and opening discs.

There’s also an emerging movement among no-tillers toward adopting narrower gauge wheels of 2½ to 3 inches instead of the 4- or 4½-inch wheels that come standard on most major planters.

Some farmers are also seeking narrower gauge wheels to reduce the amount of residue they’re running over. Other farmers feel narrower wheels improve seed-depth consistency because they do a better job following the contours of the soil surface than wider tires.

“Guys are already putting narrow gauge wheels on single-disc drills so they can leave more residue standing, which is more important in drier regions to slow air movement and conserve moisture. The end result is better depth control,” Needham says.

But he adds, “Narrow rows or higher speeds are going to require a narrow-included-angle row cleaner, and if you bring the angle down with the row cleaner, you will need narrower wheels because the row cleaners won’t clear as much of a swath.”

With larger gauge wheels — especially with no-till planters — the machines are running over root balls, root masses and other debris, causing too much opener bounce that results in seed-depth variation, says Tom Evans, vice president of sales at Great Plains Mfg.

Even with row cleaners, the root crowns and root masses may not be tossed far enough to escape the wider path of a 4-inch gauge-wheel tire.

Another problem is that gauge wheels that are worn out or improperly adjusted cause them to pull away from the opening discs. This may allow mud, stones, residue or other debris to get between the wheels and discs, slowing the disc down and causing them to push soil.

That can keep growers from getting a true ‘V’ seed trench and consistent depth placement, Evans says. That can hurt farmers where it counts — in their wallets.

“I remember for years people telling me with drills that if you see some seed on top of the ground, that’s OK,” Evans says. “That’s not OK with any seed. And every farmer seems to believe that even emergence in corn is critical, but in soybeans it’s not that big a deal.”

Years ago, he points out, Great Plains Mfg. was involved in a plot study with emerged soybeans that were 50, 100 and 150 heat units late — 2.5 to 7 days — and the soybeans that were only 2.5 days late still only had half the pod count.

“Even emergence in soybeans is critical, and the only way to have emergence the same is having them planted at the same depth.”

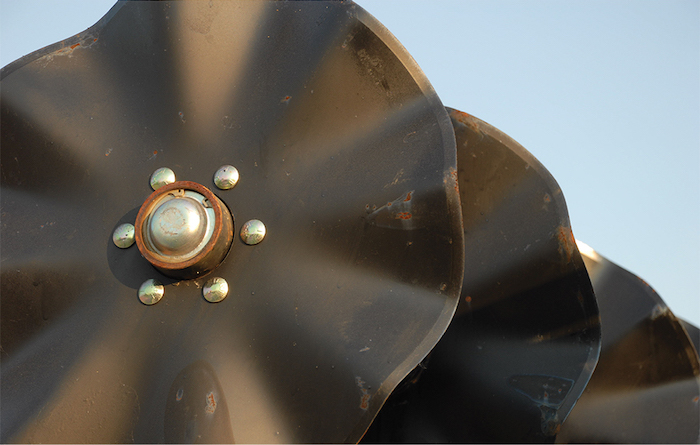

No-Till Coulters

Coulters were hailed many years ago as one of the critical equipment developments that made no-till possible. But the use of coulters on planters has declined in popularity a great deal in the past few decades.

In 1991, a No-Till Farmer survey showed that a vast majority of no-tillers — 94% — utilized coulters on their planters to slice through surface residue ahead of seed openers and, in some cases, work a little bit of soil as well.

By contrast, data from the 2024 No-Till Operational Benchmark Survey indicates just over 39% of no-tillers use them today.

Dave Dum, a planter maintenance expert with equipment dealer Binkley & Hurst, says this shift is largely due to improvements in other planting technologies. “In the past, we thought that to no-till we needed a coulter, but in fact a lot of farmers can do the job without them — especially with air bags and hydraulic down pressure,” he says.

Thompson says if a farmer tell him he wants to use coulters, he asks why.

“A lot of farmers are just using them because they’ve always used them. But we’re not running 1980s planters anymore,” he says. “Today we have hydraulic down forces that are automated, we have very heavy row units and heavy planters with plenty of weight on the tool bars to hold them down.

“Some of the original reasons why we needed coulters — to loosen the ground and allow us to penetrate better and to get loose soil to close the seed trench — we’ve replaced all of those things with better ideas.”

While neither Dum nor Thompson are enthusiastic about coulters, they acknowledge that there may be situations and soil types where farmers might find having coulters on a no-till planter to be beneficial and they both say that sometimes the effectiveness depends on how coulters are being set up and used.

“A coulter, especially if it’s running deeper than the seed opener, will cause issues. It shouldn’t run deeper than the seed opener blades or it can cause a false bottom in the seed trench,” says Dum, adding that a false bottom can lead to air pockets that dry out the soil, causing uneven seed depth and emergence.

Thompson adds that running coulters too deep frequently leads to soil being pulled out of the ground. “This can cause soil plugging around rows cleaners or gauge wheels, which can actually change the row unit depth,” he notes.

Both Thompson and Dum concede coulters will lessen wear on seed opening discs and possibly smooth out the path for them.

“Working the ground a little can make it easier for the seed opening discs to form the trench,” says Dum. “If you’re running a coulter, it’s doing a lot of the harder work of loosening a little ground for the seed opener blade following behind.”

Dum says one instance where he sees coulters as potentially beneficial is in heavy clay soils.

“I like a 13-wave or a turbo coulter blade in heavy clay. But when it gets wet, they can pull wet dirt out of the seed trench,” he warns. “I don’t like bubble coulters because they smear the sidewall too much, which is one reason I think some farmers go away from coulter blades.”

Some argue that coulters can be helpful in situations where residue is abundant or unevenly distributed in front of double-disc seed openers. But Thompson says that in those cases having row cleaners is more important.

“Anytime you have something penetrating the ground, if you don’t move the residue first, then you run the risk of just pushing it into the seed slot, or hairpinning,” he says.

For no-tillers who use coulters, research from Iowa State University suggests focusing on keeping coulters sharp may be more important than worrying about what kind of coulter to use.

Read More: 6 Tips for Maintaining No-Till Coulters

Tests conducted by ag engineers Chang Choi and Donald Erbach comparing smooth, rippled, notched and fluted coulters showed little difference between them when soil and residue conditions were the same.

Most tests with the coulters were run at 19-22% moisture, and at soil compaction levels similar to those found under no-till field conditions.

Smooth, fluted, rippled and notched coulters of 16 inches in diameter were tested along with an 18-inch rippled coulter and 18-inch sharpened, rippled coulter.

Tests were conducted at a speed of 2.8 mph and the coulters were operated at 1½- and 3-inch depths.

The coulters were run through corn stalks collected in the fall prior to corn harvest. Stalks were cut into 1-foot lengths, set in water to provide three levels of residue moisture content, and placed on the soil surface perpendicular to the coulter path at distances of 6 inches, 1 foot and 2 feet between stalks.

The percentage of corn stalks sheared was not affected by coulter type, but was affected by moisture content of the stalks, researchers say. The dry stalks were cut easier than wet stalks.

As the moisture content of stalks increased from 13% to 67%, the percentage of sheared stalks decreased from 89% down to 33%.

Stalk-shearing ability of the sharpened coulter was superior to that of other coulters. More than 90% of wet corn stalks were sheared by the sharpened coulter — even at the low-soil-strength level. The percentage of stalks sheared was a little greater for the large coulter, but not significantly.

As the coulter depth increased from 1½ to 3 inches, the percentage of sheared corn stalks increased from 77% to 87%. With 2-foot spacing between stalks, the amount of sheared corn stalks increased with greater depth.

“The coulter type had no significant effect on draft force, nor on percentage of corn stalks sheared,” say the ag engineers. “Draft force on the coulter was influenced by operating depth, size and soil strength. Angular velocity of the coulter was directly related to coulter size, travel speed and soil strength, but was not influenced by depth.”

The researchers conclude by saying the percentage of corn stalks sheared was greatly affected by sharpness of coulter, moisture content of the corn stalks and soil strength.

No-Till Seed Firmers

Another important piece of equipment on no-till planters, for those who feel a need for them, is a seed-firming device.

Seed firmers ensure seeds are pushed down and properly spaced into the seed furrow to optimize seed placement and germination.

While some early on scoffed that these firmers were “just a piece of plastic,” the Keeton Seed Firmer — pioneered by southern Kentucky no-tiller Eugene Keeton — has been instrumental in helping no-tillers maintain seed-to-soil contact.

After that, Schaffert Mfg. introduced the Rebounder, another version of a seed firmer that pushes push seeds into place. Those products dominated the early market.

Enhancements to seed firmers have continued, as they were outfitted to allow liquid fertilizer to be applied into the seed trench during planting to enhance seedling vigor and growth.

In soils where more pressure is needed at the seed location, new developments like the Mojo Wire from Exapta Solutions provide up to five times more pressure than the seed firmer can provide by itself.

Precision Planting unveiled the SmartFirmer sensor, measures the amount of moisture available to the seed, so growers can adjust planting depth correctly and have a consistent crop stand. In recent years, the Flo-Rite seed firmer emerged as another market option. In all, 2024’s No-Till Farmer Benchmark study shows 65% of respondents using seed firmer technology.

Planter Upgrades

Deciding which, if any, upgrades to make to no-till planters depends on individual needs.

Farmers with stand establishment issues related to planting depth and sidewall compaction would most benefit from newer downforce technology. This can ensure consistent seed placement through denser residue and can improve corn emergence uniformity. Especially when planting into variable or wet soils, downforce technology is an investment that pays for itself.

Similarly, seed meters, seed delivery systems, row cleaners and closing wheel technology can help create reliable stands. High speed delivery systems can add capacity per day across a wide range of soil conditions but may require tillage for a more level seedbed.

When choosing upgrades, it’s important to reflect on past planting seasons and stand establishment periods to determine what the limiting factors were and how potential upgrades might address that limitation.

Related Content:

- Row Cleaners: Coming Of Age: Engineering improvements and on-the-go adjustment are making it easier for no-tillers to clear residue from the row and improve seedling emergence, crop stands and yields.

- The Final Act: Closing The Seed Slot: Field variability, tougher trash and growers’ early-planting ambitions drive improvements to planter closing wheels used in no-till fields.

- Narrow, High-Tech Gauge Wheels Tackle Plugging, Emergence Issues: New materials and designs for depth-gauge wheels can help growers improve seed-depth consistency and emergence in tough no-till conditions, and possibly increase yields.

- Do No-Tillers Need Coulters Anymore? These row-unit stalwarts were once essential for no-tilling. But with today’s advances in planter technology, are they still necessary?

- Winter Maintenance Tips for Your No-Till Planter: Check these wear point fundamentals & non-wear points on your no-till planter to ensure it’s ready for spring.

- 11 No-Till Planting Tips: Cool and muggy conditions make it extra important to pay attention to details for successful no-till planting.

- Planting Season Challenges No-Tiller's Planter, Patience: 2023 Conservation Ag Operator Fellow persists through planting problems using highly modified no-till planter & trademark flexible thinking