Thanks to the 2018 Farm Bill, industrial hemp is no longer classified as a controlled substance and appears poised to become a marketable cash crop for U.S. farmers.

Canadian growers have been growing hemp since the 1990s and supply much of the material for hemp-based products made in the U.S., though China is also a big supplier.

Estimates and expectations for U.S. income potential are high, largely due to a growing global demand for CBD (cannabidiol, a naturally occurring compound found in the flower of the hemp plant) oil and other hemp-based products. While 2017 hemp sales in the U.S. were roughly $800 million, Hemp Consulting Group cites estimates of a $10.6 billion dollar marketplace worldwide by 2025.

While that sounds promising and many agree, Bryan Parr, farmer and agronomist with Legacy Hemp in LaFarge, Wis., suggests tempering expectations a bit.

NO-TILL TAKEAWAYS

- Due to grain hemp’s fibrous nature, use a roller in spring to flatten the remaining stalks and get the plant material to the ground.

- Planting hemp for grain early only produces a taller plant that may be difficult or impossible to harvest with a combine.

- Follow hemp with corn rather than soybeans to harvest above the ground and keep from gathering too much fiber in the combine.

“I agree with the potential, but we’re getting caught up in the large numbers and I’m not certain about the time frame,” he says. “The farmers are hearing that markets are growing about 10-20 fold every year, but remember that we’re starting from basically nothing. So even though there’s a lot of potential, it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Possibilities and Practices

While hemp can be developed into food, cloth, rope, building materials, oil and thousands of other material goods, producers will mainly be focused on growing hemp either for grain and/or fiber, or CBD — and the rules, guidelines and growing practices are starkly different depending upon which crop you wish to raise. One thing they have in common, though, is a preference for hot, sunny well-drained conditions.

While hemp was once a major crop grown in the U.S., current-day research on U.S-grown hemp is limited to a handful of pilot programs in states such as Kentucky, Colorado and Oregon, and there is much yet to be learned about how best to grow, harvest and process the crop. For no-tillers wishing to try raising this crop, experts say they should seek out other farmers who have experience with the type of hemp they’re interested in growing.

Hemp For Grain and Fiber

Hemp grain is gaining attention in the whole foods market. It’s high in protein and Omega fatty acids, and as more people are introduced to it is gaining popularity. And according to Parr, the good news for no-tillers is that grain and fiber hemp is grown similarly to other grains. Farmers already growing corn or wheat will be well-positioned to integrate hemp into their rotations.

Most farmers will want to use a grain drill to seed the crop in narrow rows, about ½ inch deep at approximately 30 pounds per acre Parr says, noting it’s very important the seed doesn’t get planted too deep. In sandier soils, seed can go as deep as ¾-1 inch; in heavier clay soils it should be planted a little shallower. A planter is also an option utilizing the grain/sorghum plates.

He recommends 7½ to 15-inch row spacing but says wider rows can work, too. The main goal of the narrow row spacing is weed control.

SLOW GROWTH PHASE. The most critical time for weed control is the first 30 days, when the plants grow slowly and haven’t yet canopied. Having a good burndown program will provide the necessary control, but it won’t fly if the processor requires organic production.

“We can be successful with 30-inch rows, but we don’t have herbicides for this crop and the narrower the rows, the quicker we are to canopy. Once it’s planted, this crop is very competitive with weeds,” Parr says, adding that even in Canada where they’ve been growing hemp for two decades there are only a few herbicides labeled for it because there are hardly any weeds that can compete with it.

“Especially on the conventional production side, we have no use for an herbicide. Organic farmers struggle a little more with weeds but there are other methods that can help them deal with weed pressure.”

The primary time weeds are an issue is during the first 30 days of plant establishment — the period Parr calls the “slow growth phase” — where plants only grow 8-12 inches. During the next 30 days, hemp hits its “rapid growth phase” where it grows another 2-5 feet. Parr says it’s imperative farmers have good weed control in the first 30 days to ensure weed-free growth during the following 30 days, because “there really isn’t a weed out there that can compete once it’s hit its rapid growth stage,” Parr says.

Hemp raised for grain or fiber is susceptible to white mold, especially during periods of high moisture and cool temperatures, and for the time being there aren’t any sprays that can be used to combat it due to current labeling restrictions. It’s possible that fungicides currently used to control white mold in soybeans will be labeled for use in hemp in coming years but they aren’t available yet. Insect pressure tends not to be too much of an issue. Japanese beetles are said to like the pollen of the male plants but they produce so much pollen they aren’t actually much of a problem, Parr notes, and as soon as the males shed their pollen they die and the beetles lose interest.

Parr finds that following a similar fertilizer program as used for corn gives good results, so he recommends a split application of 120-150 pounds of nitrogen (N) per acre, 40-70 pounds of phosphorus (P) and 60-100 pounds of potassium (K).

NO-TILL WEED CONTROL. Once the hemp plants hit the “rapid growth phase,” they shoot up an additional 2-5 feet, creating a thick canopy. Aside from rapid growers like giant ragweed, most weeds can’t compete with hemp and won’t be a problem.

Because hemp is a photoperiod-dependent crop — which means it doesn’t start flowering until the days start getting shorter after summer solstice — hemp for grain is best planted in May or June. In more southerly states the temptation might be to plant earlier, like late February or March, “but the only thing you’re going to do by planting that early for grain is end up with a taller plant, which makes it almost impossible to harvest with a combine” says Parr.

“When growing hemp for fiber you want a taller plant because you can harvest with forage equipment rather than a combine. Plus, you want a taller plant that will produce longer fibers, so the ideal time to plant for fiber is the same time you’d plant other small grains: generally sometime in April.”

Harvest Hurdles

According to Parr, harvest is the most challenging time for producers growing hemp for grain and fiber because there tends to be a lot of fiber wrapping arounds shafts and bearings in the combine and forage mowers because the fiber is so tough and durable.

“It simply doesn’t want to break. And the drier the plant becomes, the higher the potential for the plant to wrap around any moving parts,” he says. It’s not uncommon for hemp growers in Canada to have combine fires as a result of fiber wrapping.

WHITE MOLD. Not many pathogens affect hemp, but white mold can compromise it, especially during periods of high humidity and cool temperatures. With no fungicides currently labeled for use with hemp, white mold can infect plants, causing die-back.

For grain harvest, which generally runs from late September to early October, Parr’s recommendation to reduce fiber wrapping is to bring as little fiber as possible into the combine, cutting the grain heads only. This limits the fiber intake to 8-12 inches, which won’t wrap around a shaft as readily as an entire 4-foot plant would. Parr recommends using a roller-crimper to roll the remaining stalks and plant material to the ground. Due to the plant’s fibrous nature, it’s best to manage the stalks in the spring.

Another strategy to reduce wrapping is to harvest the grain at a higher moisture, although Parr warns hemp’s high-moisture oil seeds have a tendency to go rancid fairly quickly. “Generally, once the farmer has a full tank in the combine he has about 4-6 hours before it spoils. So he has to get it on an aeration bin within 4-6 hours to avoid spoiling,” he says.

If a farmer has on-farm storage, any forced-air bin should work for hemp.

“The biggest issue I see is farmers not having their own cleaning equipment. Since it’s harvested at a slightly higher moisture, the stem and leaf material is still fairly green and it’s easy to get a fair amount of foreign material into the grain,” he says. “That needs to be cleaned out so it will adequately dry in the grain bin.

“Once it’s combined it needs to be run through a grain cleaner before it goes into the grain bin so we have unrestricted air flow. The leaves and stalks will stop air from flowing, which can cause hot spots in the grain that leads to spoilage.”

Parr says hemp grown for fiber is usually harvested earlier than grain — right at pollination, which is towards the end of July to early August in the Midwest. But it is possible to harvest the fiber from a grain crop after the combine runs through. Using a sickle mower instead of a disc mower would help that process and alleviate some of the worry about wrapping.

Parr stresses that if no-tillers want to harvest the fiber after combining the grain, it should be done within 2-3 days of combining, otherwise it should stay in the field until spring.

In fact, he says, there are a couple of companies buying the fiber after the grain has been combined but they, too, are recommending farmers cut the stalks down and bale them in the spring. “Not only are the fibers easier to manage in the spring, but also the stalks break down during the winter, making it easier for the processors to separate the fibers,” he explains.

Parr suggests following hemp with corn rather than soybeans. “After hemp, we want a crop that harvests above the ground, that way you won’t run the risk of gathering too much fiber into the combine.”

No-tilling into hemp residue can be a challenge, he says, as there are so many moving parts on a no-till planter with row cleaners, coulters, disc openers and closing wheels that bring a higher chance for fiber to wrap. “It should be a little easier in the spring,” Parr says, “because the winter weather will have broken down a lot of the stalk material. But it can still be an issue. I think the jury is still out in terms of exactly how to deal with all that extra fiber.”

"In Canada, where they’ve been growing hemp for two decades, there are only a few herbicides labeled for it because there are hardly any weeds that can compete with it…” — Bryan Parr

According to Parr, variety trial data from the University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University shows that for grain, conventional farmers are harvesting 1,400-1,500 pounds per acre, while organic farmers are averaging 600-1,000. Conventional pay price for grain is approximately $0.50 per lb. and organic pay price is about $1.00.

“There’s been a lot of hype about farmers being able to make a ton of money with hemp, and while there are some farmers making a lot of money, the reality is we’re not trying to overtake the corn and soybean market. We’re trying to supplement that market,” Parr says. “That market is volatile, it’s been down and we’re looking for another crop that will let farmers spread their risk around. We’re not going to get them rich by growing this crop, but we can help them supplement their income when downturns happen.”

There are several companies, Parr’s included, that are working with farmers to both supply them with either seed or plants (often referred to as genetics) and also provide contracts to buy back the harvest.

Every source interviewed for this story stressed the importance of lining up a contract for your harvest before planting. There aren’t many processors out there yet and growers must ensure they have a market and understand the expectations going in or risk a total loss on the crop.

Growing CDB hemp

Much of the current interest in growing hemp revolves around the CBD varieties. The CBD sector is growing the fastest and is gaining the most momentum. A lot of anecdotal study results suggest CBD oil is beneficial to human health, especially in reducing seizures and anxiety.

Joseph Sisk of Hopkinsville, Ky., has raised hemp for CBD in the Kentucky Department of Agriculture’s pilot hemp program for the past 3 years. In 2018, Sisk and his partner, Todd Harton — both of whom have backgrounds in tobacco production — grew 200 acres of the crop.

IRRIGATION OPTIONS. While hemp likes hot, dry conditions, irrigation may be needed, especially during the hottest parts of the summer. For some, irrigation pivots will do the trick, while others may want to try another method, like drip tape irrigation, to drierct the moisture to the roots.

While sharing their experience, Sisk is quick to point out the industry is very new, there are no standard practices and everyone is doing it differently. “The people who are dealing with it are really working through it each year,” he stresses.

With CBD hemp, growers should be sure they’re getting feminized seed or clones from reputable companies because the female plants are the ones that create the flowers that contain CBD oil.

Ryan Davidson, genetics specialist with Sovereign Fields in Oregon, says as the industry is growing, “farmers have the opportunity to align themselves with companies that have registered genetics that have been run through university testing or some form of rigorous analysis.”

Sovereign Fields has been working with university pilot programs since 2014 to breed genetics that will be compliant with the evolving market.

Manual Labor

From late-May to the end of June, Sisk and Harton use a transplanter — the same kind as used for tobacco or vegetables — to set transplants into strips that have been prepared with a strip-till machine.

Sisk says they have tried row spacings between 30 and 60 inches, most recently landing on 40-inch rows because it matches the tobacco equipment his partner uses. Plant spacing is determined by the processor and varies from 1,500 plants per acre to 4,000 plants per acre.

Sisk and Harton use commercial fertilizer and Sisk explains again that most of the protocols are dictated by the processor. They’ve been experimenting with different approaches, doing some completely pre-plant and some split applications.

At harvest, while some growers are stripping the plants with a combine and others are chopping the plant material, Sisk and Harton harvest hemp by hand, cutting each plant at its base. It takes them 4-6 weeks to complete harvest.

“Most people are transporting CBD hemp on wagons to a clean place where it’s out of the weather and they can either stack it loosely or hang it up to dry,” Sisk explains.

Most processors require that the hemp plant be completely dry before being delivered. Drying the hemp takes a few weeks, depending upon the time of year, the temperature and the drying method.

“Most hemp is being dried naturally, by air. There are some new machines that have been built to mechanize the process, but I haven’t personally had contact with those yet. They just haven’t come to market yet,” Sisk says.

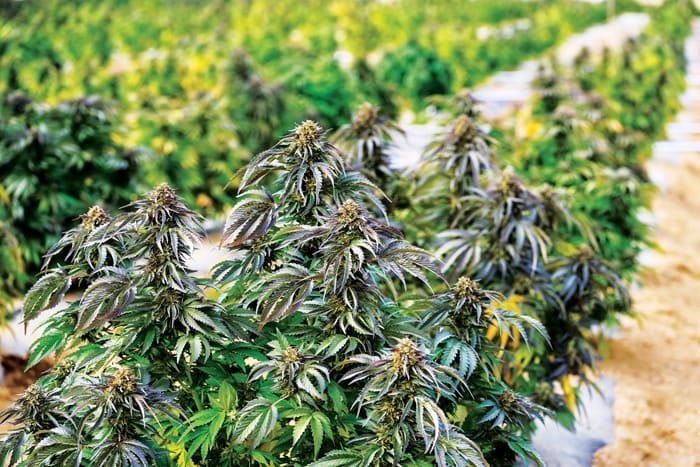

CBD hemp tends to be shorter and bushier than hemp grown for fiber, so Sisk says most people growing for CBD end up destroying the remainder of the plant by burning it or chopping it after the flowers have been harvested.

As with hemp grown for grain and fiber, plants will be tested for the level of THC and it can’t exceed 0.3%. The CBD level is the other key factor and processors are often looking for levels to be at 10% or higher. Depending upon how the plants are harvested and processed, they can produce levels as high as 20% or more.

Generally, producers are paid based on the percentage of CBD, from $2.50-$4 per percentage point and they can produce on average 4,000-6,000 lbs. of biomass per acre.

According to Davidson, the diet of the plant can affect CBD levels but the most important aspect is breeding.

MATURE SEED HEAD. Hemp grain matures in approximately 100-120 days. Seeds ripen from the bottom of the head to the top, and it is recommended that growers harvest when 70-80% of the seeds are ripe and the grain is at about 12-18% moisture.

“It takes a couple years and many generations to breed a plant to have the traits that create a stable line. If it’s in the registry, it means those plants have been tried and tested and reflects that plant’s ability to perform in the field and pass rigorous testing,” he adds, referring to state-by-state registration programs that farmers need to sign up with in order to grow the crop.

Market Risks

While it may be tempting to jump in and order some seed or clones, it’s important to consider some of the risks involved in growing a new crop. Hemp grain, for instance, can currently only be sold for human consumption.

"It's still illegal to feed this to livestock,” Parr explains. “It has to go through GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) feeding studies before it can be fed to livestock on a commercial basis. The University of Colorado just completed year 1 of a GRAS study but because this is a 2–3 year study process, it will be a couple of years yet before we can feed this stuff to livestock.”

This means there’s currently no secondary market for hemp grain and there won’t be for a couple of years at least, says Parr. Unlike a crop like wheat that can be sold for animal feed, if the harvested hemp grain doesn’t pass the tests at the lab, it could be a total loss.

In addition, there are no herbicides labeled for use with hemp. This will undoubtedly change now that hemp a legal crop, but for the time being no-tillers may need to get creative with weed control — though one option is to have a good burndown program prior to planting the hemp to keep weeds out of the field.

“Spraying Roundup about 5-7 days prior to planting will give you long enough control for the hemp to get to the rapid-growth phase before the weeds start emerging again. Then the weeds will get to maybe about 4-5 inches high and then they will mostly wither and die,” says Parr. But some producers are requiring organic production, which requires a completely different set of practices.

Finally, whether growing grain, fiber or CBD, farmers have to be licensed to grow hemp and their crop will be tested by the state to ensure that it is at 0.3% THC or less. Anything more than 0.3% is considered marijuana and will be destroyed.

“The grain and fiber types essentially have no more THC than corn and soybeans,” Parr says. “The CBD types are more of a concern because to get a high percent CBD content, breeders take industrial hemp and breed it with marijuana cultivars, so those are the ones that are more likely to run high on THC.”

Strong Future

Most everyone agrees that regardless of whether growers are interested in growing hemp for grain, fiber or CBD, now is a good time to get involved and test it out, even though there are some challenges.

“It’s been a good learning experience,” says Sisk. “We’ve enjoyed doing it. There’s going to be a long-term, sustainable market going forward but right now there’s not a true market developed for it. You’re either growing it for someone, like a processor, or you’re going to have to find a buyer after the fact. It’s not like a commodity where you can go discover what the price is.”

His advice to farmers interested in growing CBD hemp is to “start small and work with genetics suppliers and processors that other farmers vouch for.” He says farmers who have handled vegetables, tobacco or other labor-intensive crops like hay or straw will probably do well because they won’t be scared of the work and the need to problem solve and devise solutions to challenges they encounter.

Davidson agrees the market is strong and growing, noting that large companies like Phillip Morris are getting into the market. He adds there’s a need to create buffer zones around CBD fields because CBD plants can be accidentally pollinated by other hemp plants if they’re too close.

“The first thing a farmer should do is check with your agriculture commissioner to make sure you won’t have cross-contamination with farmers growing industrial (non-CBD) hemp,” he says.