Mitigations are being proposed as a means to offset potential risks associated with pesticide registration and ensure compliance with the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Pesticide registration in the U.S. is fundamentally governed by two statutes: the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) as administered by the U.S. EPA, and the ESA as administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service, collectively known as The Services.

When EPA assesses the potential risks associated with registering a pesticide under FIFRA in the form of a biological evaluation and concludes that the action may affect and is likely to adversely affect a threatened and endangered species, the agency is required to enter into formal consultation with The Services. The Services then assess whether the action is likely to jeopardize the existence of listed species or adversely modify corresponding critical habitat. Failure of the EPA to consult and/or failure of The Services to assess results in non-compliance and creates opportunities for lawsuits, which essentially brings the process to a standstill.

In order to address the backlog, create efficiency and meet court-mandated timelines, the EPA has proposed a strategy to implement upfront mitigations to offset potential risks and ensure compliance. This sounds like a viable concept in theory, but in practice, its feasibility is unclear.

More Questions Than Answers

Under this scenario of upfront mitigations, growers would essentially be tasked with selecting mitigations from a menu or picklist in accordance with a rather arbitrary point system to be able to use a given pesticide product. However, this brings up new questions, such as what mitigations, how many, where and when?

The answers to these questions are not obvious because the justification for them is also unclear, though it is primarily rooted in a lack of sophistication in the current ecological risk assessment process for endangered species. The prevailing methodology is highly prescribed, relying on standard inputs and models, as well as layers of conservative assumptions. This can be useful when the objective is to ensure that you don’t conclude a pesticide registration poses unacceptable risks when it does, but the downside is that you are more likely to conclude significant risks when there in fact may be none.

Generally, this is addressed in a tiered framework where lower tiers are conservative and unrealistic, and higher tiers are more sophisticated and integrate higher-tier studies, methodologies, models and information. The problem is that the higher tiers are rarely — if ever — explored, primarily because they don’t fit very neatly inside the screening-level box. Consequently, conclusions predicated on lower tiers don’t characterize potential risks appropriately, accurately or realistically to the level of detail required to adequately inform mitigations.

What It Means for No-Tillers

In a nutshell, the current risk assessment process results in the potential for inflated estimates of risk, which result in exaggerated need for mitigation. This is troublesome for production as the degree and nature of mitigations may be unwarranted and/or unnecessary. Potential mitigations include alley cropping, constructed wetland, contour farming, cover cropping, grassed waterways, mulching with natural materials, no-till, riparian buffer zones, strip cropping, terrace farming, vegetative filter strips and field borders, and ponds for water and sediment control. However, the full suite of options has not been thoroughly inventoried, the mitigating potential to offset potential risk has not been adequately evaluated, and the economic and agronomic feasibility has not been comprehensively assessed.

Some options, such as no-till, cover cropping and grassed waterways, are commonly practiced and broadly applicable, whereas others like field borders or riparian zones require potentially significant investment and land allocation away from production. As a result, the consequences for farming and farmers could be significant. Additionally, the potential benefit to endangered species recovery and status is unclear as pesticides are generally not considered a primary driver for species decline.

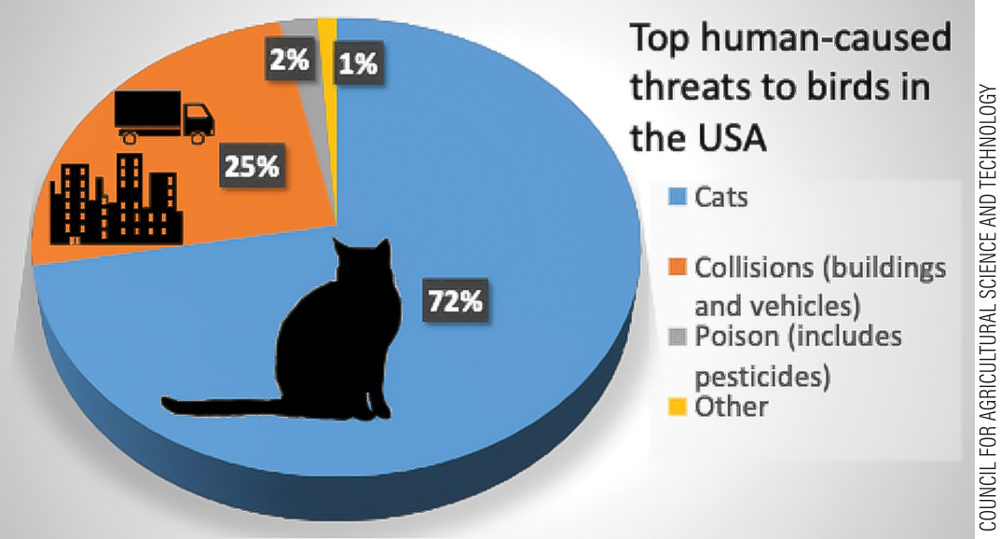

For example, the no. 1 cause of bird mortality in the U.S. is domestic and feral cats, which account for 72% of annual losses. Collisions with buildings and vehicles contribute another 25%, while poisons are responsible for 2%. Similar trends exist for mammals, fish and terrestrial plants. A question to ask might be why are we investing so much time and resources into regulations with potentially significant collateral damage to agriculture, rather than focusing on the primary drivers like invasive species, habitat loss or climate change?

Many mitigation options are generally beneficial, especially for runoff control and erosion. However, within the context of the Section 7 consultation process, it would seem that time and resources would be better spent on spay and neuter programs, among other things.