Editor’s Note: To commemorate no-tillage’s 60th fall harvest on the original Young farm, we turn back to Kentucky’s no-till home.

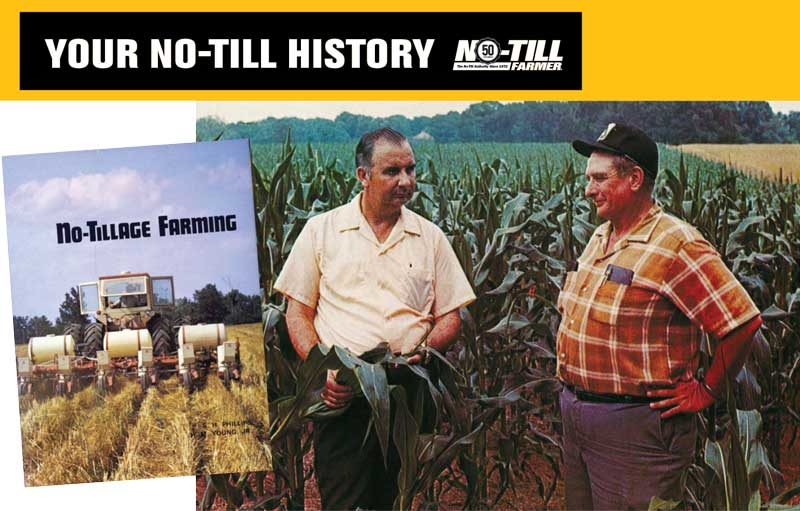

University of Kentucky Extension Director Shirley H. Phillips and No-Till Farmer Harry M. Young, Jr. authored No-Tillage Farming, the 1973 book by the fledgling No-Till Farmer publication (which also celebrates its 50th year this month). The text that follows is the pair’s introduction to their book, regarded globally as a seminal piece of literature that was key for understanding the then-novel no-tillage method. You’ll find humility in their words about the yet-unproven no-till practice as well as a window into current thinking about farming’s future – exactly 60 years ago, as their text was sent to the printer.

The book saw several printings and was also translated into Portuguese, where it was an indispensable reference guide for South American farmers for whom tillage and other high machinery, fuel and labor expenditures were not an option. Collectors can still find few copies of the 224-page book, available in both hard- and soft-cover on eBay.

– Mike Lessiter, President

The plow is as American as the Fourth of July. Such famous farmers as Thomas Jefferson and Daniel Webster helped perfect it, and today’s politicians still speak of realigning our national priorities in terms of “swords into plowshares.”

The sword had ceased to be an important implement of warfare long before America was colonized, but the plow is a cornerstone of America history. For nearly two centuries it has been an appropriate, and very literal, symbol of the nation’s domestic priorities.

Economic growth and geographical expansion during the first century of U.S. history literally followed the development and westward advance of the plow through the prairie and onto the plains. Then, as the agricultural society gave way to an industrialized society, the plow lived on as the key element in an increasingly mechanized and efficient American agriculture.

Plowing’s Purpose Questioned

In 1943, when Edward H. Faulkner leveled criticism at the plow in his Plowman’s Folly, he received very little support from scientific circles. However, the agricultural sciences seemed at a loss to disprove his statement that “no one has ever advanced a scientific reason for plowing.”

“Conservationists were successful in getting large numbers of farmers to adapt soil and water conserving practices ... however, the plow is still here today, larger and more devastating than ever.”

In the early days of American agriculture, there were definitely economic reasons for plowing, if not scientific reasons. However, any economic justification of the plow was certainly diminished during the great agricultural depressions of the 1920s and 1930s. Faulkner had also witnessed the devastating floods and dust bowls of this period, and though he didn’t have a workable alternative, he recognized the plow as a major cause of soil erosion.

Government response to the problems of wind and water erosion began in 1935 with the formation of the Soil Conservation Service. Conservationists were successful in getting large numbers of farmers to adapt soil and water conserving practices; however, the technology available helped only to minimize the hazards of tillage rather than eliminating it. During the ‘50s, the conventional moldboard plow began losing some of its following to the chisel plow, disk plow, stubble mulcher and other forms of primary tillage tools.

Plow-plant and wheel track planting systems gained isolated acceptance, and some early experiments were conducted on eliminating all tillage. The development of workable no-tillage farming systems is traced on later pages. However, the plow is still here today, larger and more devastating than ever.

To farm without any tillage is an unfathomable concept to those who have not learned to farm without plowing, even though total inversion of the plow layer before each crop represents a huge investment in equipment, labor and fuel. Ohio scientists estimate that the amount of horsepower expended in such tillage practices each year in the U.S. results in the movement of enough soil to build a superhighway from Los Angeles to New York.

The fact that the majority of this tillage is unnecessary is not the major concern of conservationists and environmentalists. Their prime concern today is with the effect this extensive tillage has on the environment. Over-tilled soil is unprotected soil, and because of the seasonality of tillage operations, the soil is unprotected during that period of the year when rainfall and wind velocity are usually the greatest.

This vulnerability of soil to wind and water erosion has led to pollution by soil movement, and the intensive chemicalization of agriculture during the last two decades has resulted in pollution by chemicals as well. The consequence has been enactment in many states of rigid statutes to control the amount of both soil and chemical runoff. These anti-pollution laws may well provide the impetus that will eventually lead to the demise of the plow.

Force of Habit is Strong

Total elimination of the plow, or of any other tillage implement, is neither necessary nor advisable. However, it seems irrefutable that some control of indiscriminate stirring and restirring of such an important natural resource — and potentially hazardous pollutant — as soil is advisable.

Prescription tillage recommendations, ranging from the conventional plow, disk and harrow method to absolute zero tillage practices, could be developed to offer optimum benefits as well as maximum protection for every soil type, crop, slope and climate. A monumental task, indeed, but one whose importance will become more and more apparent in the near future.

“Ohio scientists estimate that the amount of horsepower expended in tillage each year in the U.S. results in the movement of enough soil to build a superhighway from Los Angeles to New York.”

While many growers no longer have a scientific reason for the extensive tillage operations they practice, they do have, or at least feel they have, economic justification. In most instances, however, eliminating at least some of their tillage operations would have a positive effect on production costs without an adverse effect on yields. And in many cases, eliminating all tillage, with the exception of that necessary to place the seed in the ground, would reduce production costs drastically and, in many instances, improve yields as well.

Farming in the Year 2000

Nevertheless, the force of habit is strong. Even visionary scholars depicting agriculture in the year 2000 have found it hard to dispense with their treasured tillage tools. One such fascinating display of foresight described a giant, 400-horsepower turbine tractor, controlled electronically from the farmer’s command tower, pulling an array of implements beginning with a 200-inch plow and ending with a planter that metered seed electronically.

Any farmer who attempts that system in eastern Kentucky will have to use central Ohio to turn it around. The command tower concept is indeed visionary, and possibly a 400-horsepower tractor with companion-size tillage tools will be necessary to loosen the compacted soil following repeated traffic from a 400-horsepower tractor with companion-size tillage tools.

Agriculture in the year 2000 has also been envisioned as a series of huge glass domes with completely controlled environments, each featuring its own weather system as well as supplemental irrigation from the runoff from the dome. As long as the screen door was kept closed, insects would never be a problem, and the controlled environment would allow crop production to continue endlessly, even in northern climates. Planting and harvesting would be calendarized in order to permit maximum use of the giant 400-horsepower turbine tractor with its trail of massive tillage tools.

With this caliber of inventiveness working on the future of agriculture, it may seem futile to advocate a cropping system that approximates the methods used by the Indians when the Pilgrims arrived in the New World. However, to the grower now profiting from the elimination of tillage, dreams of bigger or faster tillage tools are nightmares.

“Coming generations of farmers will find it hard to understand why their forefathers found it necessary to turn, stir, sift and comb every acre of soil every year.”

No-tillage farming is not without its problems, but we have yet to find one that would approximate a power failure in that electronic control tower or a ventilation failure in a thousand-acre dome. And although no-tillage does demand extensive management ability, it doesn’t approach the caliber of management required to change a flat tire on a 400-horsepower turbine tractor or to troubleshoot a short circuit in an electronic control tower.

Just Getting Started in 1973

The fame of the late Shirley Phillips and Harry Young was only beginning in 1973 when No-Tillage Farming was published by No-Till Farmer. Below are the summaries from the “author’s page’ bio’ in the book. For more complete information visit www.No-TillFarmer.com and read No-Till’s Pioneering ‘Dynamic Duo’.

S.H. Phillips, Assistant Director of Extension for Agriculture, University of Kentucky. Shirley Phillips has been on the University of Kentucky staff since 1948., first as a County Extension Agent, then as an Extension Agronomy Specialist before becoming Assistant Director of Extension for Agriculture. A native of Kentucky, he earned both B.S. and M.S. degrees in Agronomy at the University of Kentucky. He’s been active in no-tillage development since 1963 and has authored numerous articles and papers on the subject. He has lectured on no-tillage before many farm, commercial and professional groups, and has been instrumental in organizing numerous no-tillage demonstrations, meetings, tours and seminars. In 1968, he was honored as Man of the Year in Kentucky Agriculture by Progressive Farmer magazine.

H.M. Young, Jr., No-tillage farmer, Christian County, Kentucky. Harry Young grew up on the Herndon, Ky., farm he now operates. After earning his B.S. and M.S. degrees at the University of Kentucky, he spent 9 years aa s Farm Management Specialist for the University before returning to the family farm in 1954. He began experimentation with no-tillage techniques on 7/10ths of an acre in 1962. To date, more than 10,000 visitors have viewed no-tillage crops on his 1,235-acre farm. Through numerous papers, articles and lectures, Young has spread the no-tillage message to additional thousands. Young is a member of the Board of Directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and President of the Elkton, Ky., Federal Land Bank Association. He was named Man of the Year in Kentucky Agriculture in 1969.

We are not attempting here to belittle big tractors, remote-control farming or controlled environments for crop production. These undoubtedly will be a part of the crop production picture a quarter of a century from now, as will plows and an assortment of other tillage implements. However, coming generations of farmers will find it hard to understand why their forefathers found it necessary to turn, stir, sift and comb every acre of soil every year.

They may also find it hard to believe that blowing soil had once turned mid-day skies as dark as night, or that rivers ran black with soil and foamed white from chemicals. And the politician who speaks of “swords into plowshares” will find himself having to explain what both were once used for.

As Ideal a Method As Knowledge Allows

This book is not complete in every detail, nor can it be. Farming techniques change too rapidly for researchers, writers and sometimes farmers, to keep pace.

We are concerned here with the development and improvement of one aspect of crop production — tillage or rather — no-tillage. Although several facets of tillage are considered, the authors admit their emphasis is placed on a higher-yielding, lower-cost, soil-saving, new cropping technology, variously known as “no-tillage,” “zero- tillage,” “sod-planting,” “direct-planting,” “direct-seeding,” “no-till,” or by several other recently coined terms.

Even the most enthusiastic supporters of no-tillage farming do not claim it is the ultimate. Man probably never will attain the ultimate in cropping. However, a mass of facts indicate no-tillage farmers now may operate as near to the highest degree of effective, profitable and economic land use as can be achieved with man’s present level of farming knowledge. No-tillage is not expected to be exceeded in simplicity and overall effectiveness within the lifetimes of present generations.

No-tillage is not a substitute for good farm business management. Nor is it a cure-all — there is no such thing in agriculture.

A need exists for several tillage systems, but noticeable progress is being made toward sim-plifying tillage practices and ultimately eliminat-ing tillage on many crop farms. Therefore, we now see a large number of individual farmers in several areas achieving consistent success with no-tillage farming; the news is spreading.

One of the purposes of this book is to get no-tillage facts spread more widely and quickly to farmers and agricultural technicians interested in advancing farm technology. Perhaps, then, there will be further stimulation of research and on-the-farm testing of no-tillage techniques. Thus, those farmers already using no-tillage may be stimulated to improve their present methods.