Editor’s Note: All of history contains conflicting stories, and accounts of the first planter built specifically for no-till are no different. There was International Harvester’s failed production in the early 1950s and Allis-Chalmers (A-C) is accepted to have birthed the first successful no-till planter in 1966. History, as the saying goes, belongs to the winners.

But John Rosendahl, a long-retired A-C, Deutz Allis and AGCO service department employee, contacted No-Till Farmer (NTF) to point out an inaccuracy that may have been promulgated even before NTF was founded in 1972.

“The 600 series planter frames were not originally designed with no-till in mind,” he says. “The no-till coulters did not replace the spring teeth on the front bar until 1967.” For more on this story, click here.

Rosendahl’s story opened another rabbit hole, and another look into events in Dixon Springs, Ill., which might be regarded as no-till’s “garden of Eden,” as it influenced Kentucky’s Harry Young Jr., and countless other pioneering no-tillers. This article tells the story of the mechanic who some think built the first “real” no-till planter. It’s told by Illinois Farmer Today’s Nat Williams, with permission from the publication.

— Mike Lessiter, President

IT WAS A RADICAL IDEA, planting seeds directly into unworked soil — so radical no machine existed that did such a thing. So Donnie Morris made one.

Morris, a mechanic and ag engineer at the Dixon Springs Agricultural Center (DSAC), watched first-hand as the late University of Illinois weed scientist George McKibben experimented with the no-till concept as early as the 1960s at the DSAC.

Morris cobbled together various parts to make what some believe to be the first dedicated no-till planter design in 1966.

McKibben had struggled to test the new cropping method while planting corn into standing fescue but was willing to try virtually any planting scheme. “He even planted corn with a screwdriver, to find out if this would work,” Morris says.

One challenge was providing enough downward pressure for seeds to penetrate unplowed soil and stubble. The breakthrough came with the creation of what Donnie Morris calls a cutter-packer wheel to use on the single-row planter.

“After trying some changes to conventional planters, it was apparent that route wasn’t going to get us a good no-till planter,” said Morris, now 88, who still lives on the same southern Illinois farm where he grew up. “The problem was getting the seed in the ground. The lightweight planters designed for worked-up dirt wouldn’t penetrate sod. We decided we were going to have to start from scratch.”

Morris created a heavier press wheel but it still didn’t do the trick. The breakthrough, he says, came with the “all-winter-long” work in creating a cutter-packer wheel.

“It was nearly a foot in diameter,” he said of the cutter-packer wheel. “I put a coulter blade on the side of it that was about 3 inches bigger than the wheel. I put it on a pivot that you could adjust the height of it in relation to the opener runner.

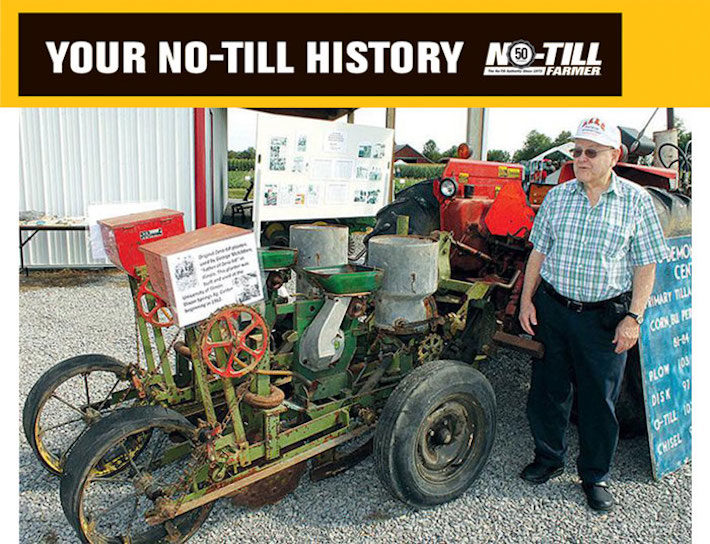

DOWNPRESSURE A CHALLENGE. The earliest work in experimental no-till planters was done at Illinois Dixon Springs Ag Center by Dr. George McKibben and his trusted mechanic Donnie Morris. Downpressure was a problem as you can see in an early 2-row planter.

SOURCE: From Maverick to Mainstream: A History of No-Till Farming

“The idea was that it would cut a slice of soil about 2 inches to the side of the runner, move it over and then close up the opening that the coulter and runner had made, then press it down on top of the seed.”

The crew tried it in the spring of 1967 and found it did the job. The machine was then hauled to the plots at Ewing Field and other places where more researchers joined in on the no-till movement.

Planter Components

Many of the components of the planter were cast-off parts from conventional machines and donated leftover items from Petter Supply Co. in nearby Paducah, Ky. The marine equipment manufacturer also provided weights used on anchors. Morris installed them on the planter to provide sufficient pressure to help push the seeds into the claypan soils of southern Illinois.

The original no-till machine was a 3-row planter, providing researchers with a handier method of planting the small experimental plots at Dixon Springs and Ewing Field. Morris built three planters and still has one in his shed at home. He also built a single-row machine, which was used largely for replacement parts.

Deere’s First Scoff at No-Till?

The university pitched the “Sod & Stubble Planter” to John Deere, which rejected it on the grounds of no-till’s insect control challenges. Morris and McKibben had the chance to apply for a patent but didn’t pursue it.

DEERE DIDN’T BELIEVE. John Deere declined to pursue Morris’s planter, citing concerns about insect control. It may have been the first time, but certainly not the last, that Deere scoffed at the no-till practice.

Patents were later awarded for inventors with similar designs, but Morris, who spent his 35-year career at the DSAC, has no regrets. Instead, he is satisfied that he played a small role in helping alleviate one of the biggest problems facing agriculture at the time — soil erosion. “I was just thankful we got no-till going and saved a lot of acres,” he says.

This article originally ran on agupdate.com.

More on the University of Illinois’ Ewing Field Demonstration Center

“There was actually pretty good ridicule for people who were trying no-till early on,” said Dennis Epplin, a former University of Illinois extension agronomist. “They said, ‘That simply can’t work. You’re doomed to failure. And besides that, you’re really making the neighborhood look ugly.’ Things have changed a great deal.”

Dennis Thompson, an extension educator who first became involved in research at Ewing in the mid-1970s, added everything fell into place for a new way of farming. Some of the earliest users were farmers in Kentucky.

“The time for no-till was right,” Thompson said. “This demonstration center [at Ewing Field] was an excellent venue to support the work at Dixon Springs, Ill. It took about 5 years for adoption of the practice to really begin. This was a tool for sloping land, good drainage, places where you wanted to avoid erosion.

“After seeing that Kentucky was adopting it, we learned the types of soils and slopes here where it would work. Now it is common not only in the Midwest, but throughout the world.”

Epplin said observation of the plot at Ewing Field provided researchers with some insight to the promise of no-till.

“There were some challenges with both crop production and water drainage in southern Illinois,” he said. “The no-till plot didn’t have those same challenges. It was clear that no-till was working pretty well. Also, it could save a bunch of time.”

— Nat Williams, Illinois Farmer Today

The 2024 No-Till History Series is supported by Calmer Corn Heads. For more historical content, including video and multimedia, visit No-TillFarmer.com/HistorySeries.