By Dhruv Sawhney

COO and Business Head, nurture.farm

The world’s population is expected to reach almost 10 billion by 2050. As our numbers swell, so too does the pressure on the agriculture industry and its farmers.

A great responsibility for feeding the world falls on India, which is the second-largest producer of staple foods like rice, wheat, groundnuts, fruits and vegetables globally.

Contributing almost 20% to total GDP, providing employment to over half its 1.4 billion inhabitants and serving as the main source of livelihood for over 70% of rural households, agriculture is also a crucial sector for India itself.

Yet it also exists as a primary contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) through deforestation, land use, and the cultivation of rice, the latter of which alone accounts for 11% of total agricultural methane emissions globally.

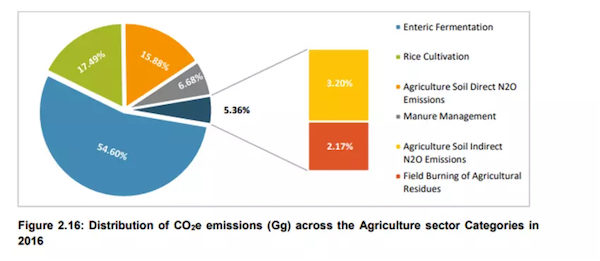

India is the world’s third largest emitter of GHG, with 74% of its carbon emissions attributable to methane from livestock and cultivation, and another 17.5% of agricultural carbon emissions derived from rice cultivation.

Every year in northern India, 23 million tonnes of paddy stubble is burned, contributing as much as 40% of New Delhi’s pollution during winter months, and an annual health and economic cost of around $30 billion.

Agriculture as a climate-positive force

During COP26, India announced its five-fold strategy for fighting climate change. Commitments made included a reduction of one billion tonnes of carbon by 2030, reducing the carbon intensity of GDP by 45% by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2070.

While agriculture is regarded as a key cause of climate change, it is also an integral part of the solution.

Take soil. Applied with the right techniques and technologies, farmland alone has the capacity to store up to 1.2 billion tons of carbon and could offset 4% of average annual GHG emissions over the rest of the century.

Soil carbon sequestration opens up new possibilities for climate-positive agriculture that delivers shared benefits, including enhanced soils that reduce fertiliser use and improve overall crop health, increased farmer resilience and prosperity as well as reduced GHG emissions.

With 52% of global farmlands degraded or disused, it is imperative that we restore the value placed on healthy soils through active interventions.

Rewarding regenerative practices with carbon credits

Carbon credits — certified emission reductions from climate-positive projects — are quickly being adopted to encourage sustainable business practices and help reach global net-zero goals. The voluntary carbon market, worth $1 billion in 2021, is now attracting the interest of global corporations.

While most projects used to generate carbon credits are related to renewable energy and reforestation, there is growing awareness around the concept of ‘carbon farming’.

These programmes seek to enhance agriculture’s role in climate mitigation by supporting offset production from soil carbon sequestration — with the ambition of trading these carbon offsets.

For instance, Microsoft recently committed to buy $2 million of carbon credits from an American farming cooperative, and US President Biden has called for a “carbon bank” to pay farmers for adopting regenerative agriculture practices.

Agriculture-related carbon credit systems have, so far, been mostly confined to large scale holdings in developed economies, where farmers have greater access to information sources, technology, and the necessary mechanisation and equipment.

However, the potential for impact in the developing world — home to hundreds of millions of farmers working small acreages — is colossal. We must establish a simpler validation and verification process of carbon credits to scale projects faster and support sustainable practices.

Democratizing innovation for sustainable profit

Technology and the private sector, too, can play a role in opening access to carbon credit systems or other carbon sinks for small acreage farmers.

Take nurture.farm, a digital platform for sustainable agriculture. It aims to preserve and enrich global soil health and utilise its untapped potential as Earth’s largest carbon sink. And smallholder farmers play a key role in this effort.

In November 2021, as part of a Crop Residue Management (CRM) programme and in partnership with the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, nurture.farm convinced over 25,000 farmers across over 420,000 acres of land to decompose their rice stubble rather than burn it, preventing the emission of over one million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

This was made possible by the distribution of ‘PUSA’ — a bio-enzyme that decomposes stubble and turns it into compost, enhancing the soil quality and water-holding capacity of fields, in turn reducing farmers’ reliance on supplementary fertilisers.

As well as a host of other tech-driven innovations, nurture.farm ensures farmers are incentivized to use its innovations by selling India’s first ever agriculture-driven carbon credits.

Other companies, such as CropIn, are using artificial intelligence to digitize and inform decision-making on the farm. By equipping Indian farmers with mobile-based advisory dashboards hosting insights around sowing, soil health, seed treatment, and weather forecasts, farmers are fostering resilience to changing climates and participating in regenerative practices — while ensuring their farms remain efficient and profitable.

Toward net-zero

India has pledged net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, and in that effort initiatives like eliminating stubble burning, equipping farmers with digital tools and other regenerative agricultural practices must become — and remain — top priorities.

New technologies and digital connectivity are already pairing with carbon credit systems to unlock opportunities for farming communities that harness the power of climate-positive agriculture, and boost their livelihoods as a result.

While work is yet needed to streamline the carbon verification and validation process, with a bespoke and integrated approach, smallholder farmers can participate in the carbon market — benefiting them and the planet.