The still “coming of age” no-till practice received two significant shots in the arm when no-tillers were tapped for influential posts in D.C. Instead of bureaucrats, the USDA smartly veered from the norm to appoint two practical farmers, Missouri’s Peter Myers and Ohio’s Bill Richards, to help convince farmers of the merits of reducing tillage.

This tale of two no-tillers shows what can be achieved when “outsiders” go to work “inside” the Beltway.

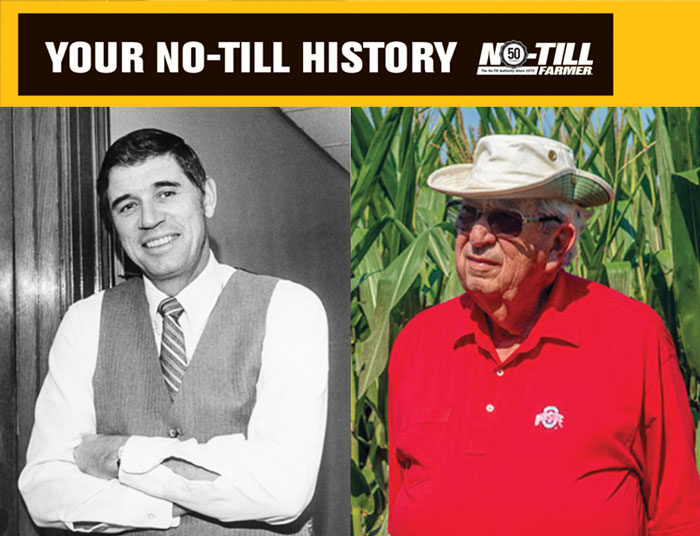

Peter Myers, SCS Chief 1982-1989

The first no-tiller tapped to be Chief of the Soil Conservation Service (SCS, now known as the NRCS) post was Peter Myers, who served from 1982-1985, and then as USDA’s deputy secretary until 1989.

RIGHT MAN FOR THE JOB. “Peter Myers, the president’s new deputy ag secretary, has just enough political naivete, just enough Missouri forthrightness and just enough sense of what is right and wrong to disarm potential critics on the outside and to win over doubters on the inside,” reports the June 16, 1986 Washington Post.

A Wisconsin native, Myers arrived in Missouri in 1955 after 2 years in the U.S. Army and began farming in the state’s southeast Delta region. He became a top farmer in the area and was recognized with a Jaycees Outstanding Young Farmer (OYF) Award in 1967, which introduced him to Illinois farmer John Block, who also received an OYF Award a couple years later and who’d become USDA Secretary in 1981. Incidentally, No-Till Farmer’s (NTF) Frank Lessiter was a judge the year of Block’s selection.

Multiple articles recount how Block’s appointment of his friend Myers to head the SCS, “infuriated conservationists and legislators,” noted the Washington Post. A 1984 United Press International article reported that Block needed a farmer in that post to convince other farmers to embrace soil conservation.

Myers was the first non-professional to run the SCS. Traditionally, soil conservationists were promoted up through the ranks to that position. While close to conservation practices, Myers later said his lack of scientific expertise was a strength, as he listened to experts and established relationships in the process. He also returned home each harvest season to help his son-in-law bring in the grain, keeping him grounded as a real-life farmer.

He expected to return to the farm depending on President Reagan’s term but was tagged for the Assistant Secretary position of Natural Resources & the Environment, and then Deputy Secretary of Ag from 1986-1989.

In a 1983 NTF article, he admitted he “botched” no-till in the early 1970s on his furrow-irrigated land. But he’d become a major champion for the process. And he didn’t mince words about conventional tillage.

“The new machinery, chemicals and techniques that have made conservation tillage possible will make the moldboard plow as obsolete as the scythe and butter churn.” Another bold statement for an agency head: “As far as I’m concerned you can take all the plows in the country and put them in the scrap iron pile.”

He maintained a belief that no-till would be practiced on the majority of U.S. cropland by 2010. Myers died in 2012, unable to see that level achieved. But he did get to see another of his lofty goals realized.

A 1986 Washington Post article lauded Myers and cited his “quixotic effort to get the plow removed from the USDA’s official logo.” Ten years later, that goal was accomplished. In 1996, the use of the Seal was relegated to legal materials only and replaced with a new logo.

Myers later served as a congressman in Missouri from 1999-2007.

Bill Richards, SCS Chief 1990-1993

The son of an Ohio farm equipment dealer, Bill Richards had listened intently to his Ohio State University professor. That is, that the plow was unnecessary.

CREDIBILITY TO BRING CHANGE. “Our role at the USDA is change,” Bill Richards, said in a 1991 news release. “The public, in both the 1985 and 1990 Farm Bills, sent a clear message — it’ll no longer subsidize practices that erode the soil or damage water quality.”

“I was determined that we didn’t need to plow and could do things in one pass. We tried the Western lister in the late 1950s and 60s, before the no-till coulter came along. In those early days, I was just trying to buy the parts we needed.”

“We went to the John Deere factory and they snubbed us, but International Harvester (IH) and Ralph Baumheckel of its Product Planning Group opened the doors for us. Ralph let me roam around the IH planter factory and pick out whatever we wanted. I’d say it was a breakthrough because Ralph followed up on what we were doing. He’d believed in the concept of the Till Planter (by R.R. Poyner and produced for 2 years at IH in the early 1950s), as a real innovation and a concept that could work.”

“Bill was one of the pioneers in the entire U.S. when it came to controlled traffic farming in the late 1960s,” says Lessiter, who brought him to speak at the first NTF conference in Hawaii in 1973, among Richards’ first-ever speaking gigs.

Richards was also a OYF recipient in the same class as Myers and the two became friends. Richards remains proud of the credit given to him for schooling up two deputy ag secretaries (Myers and Jim Moseley) on no-till.

Richards got closer to his equipment needs with a modified toolbar from Orthman (he’d met Henry Orthman at the same Hawaii conference). And then a big development arrived “when a young Jon Kinzenbaw” came out with the Kinze 24-row rear-fold planter frames in 1976. It allowed Richards to double his planting capacity in one pass. Richards was a farmer-dealer for both manufacturers.

“John Deere was selling planters by the unit at the time, so farmers could put their own planting systems together,” he says. “Around 1979, we made the commitment to ‘never-till,’ and we never looked back.”

The efficiency achieved from no-tilling with a 60-foot planter would allow Richards to expand up to 8,000 acres in the 1980s.

1985 Farm Bill Changes No-Till Trajectory

“The Food Security Act of 1985 (or Farm Bill) provided a boost to conservation tillage adoption; it aimed to reduce production on highly erodible lands and to increase the use of soil conservation practices by including them as a qualification for crop subsidy programs. Conservation tillage was one of the eligible conservation practices and had to be initiated by 1990. As a result, there was a sharp increase in the rate of adoption between 1989 and 1991.”

— Conservation Tillage Systems in the Southeast: A Historical Perspective,

Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE), 2020.

Mr. Richards Goes to Washington. The 1985 Farm Bill is what forever changed no-till, and Richards’ career. “It required farmers to cut back on erosion on highly erodible land,” he says. “Farmers everywhere were upset that the SCS said you had to no-till to get the payments. They didn’t like the SCS telling them how to farm. The SCS Chief was trying to make farmers change, but he didn’t know how to convince them to change.

“Deputy Ag Secretary Moseley knew me from the Farm Foundation and recommended me to USDA Secretary Clayton Yuetter. They needed a farmer, and if no-till was going to be part of it, they needed a farmer who was a no-tiller.”

“They didn’t know if he could get me approved by the White House, but they were influential and got me through. The Farm Bill is what got me sent to Washington.”

So in 1990, Richards was approved as chief of the SCS to serve under Yuetter and President George H.W. Bush. “I’d never had a true off-the-farm or off-the-dealership job, and suddenly I had 13,000 employees,” he says.

Richards didn’t exactly find a convinced audience upon walking in the door. “I said ‘It’s not the only conservation practice, but no-till is the fastest, easiest and best choice and farmers will do it.’”

He also found the SCS to be standoffish. “SCS’s culture didn’t work with dealers or herbicide companies.” We got that changed. Well, we got it done without asking permission, other than with Moseley, who was on our side. To meet with Monsanto management like we did was almost unheard of at USDA at that time.

“To get things done, I learned you had to treat people like they’re customers. As a farmer, I came from the customer side, and that’s how it is at the local level. But it wasn’t part of that culture in Washington,” he says.

“What the SCS Chief position did was give me a platform to ‘sell’ no-till. We went to Monsanto’s headquarters and met with their president and the whole works. They cut the price of Roundup, which was a breakthrough. We started the residue management campaign, and we got to set standards of how much had to be left on the surface.”

The years in Washington were the most exciting of his life, he says, and satisfying to see the huge leap in no-till acres. “I’m proud of the difference we made. We increased no-till and interest in cover crops by working with farmers. We greatly reduced erosion. Look at erosion charts of the U.S. from 1985-2005 you’ll see the big dip in total erosion. And if you lay a no-till chart of the same years alongside it, you can see what caused that dip.”

He is also proud to have had a lot more cooperation with EPA and Fish & Wildlife Services than typically found in a Republican administration.

Richards, widely regarded as the “Grandfather of No-Till” is a NTF Legend and No-Till Innovator Alum. At age 90, he’s mostly retired these days, but his three sons continue farming the family’s 3,000 acres of corn and soybeans in Circleville, Ohio. His granddaughter, Maria Roberts, attended the 30th Annual National No-Tillage Conference in January 2022.

WEB-EXCLUSIVES

- A selection of Bill Richards content is posted at www.no-tillfarmer.com/BillRichards

- Myers: From The Archives: No-Till Gets More Attention Among Soil Conservationists (August 1982 No-Till Farmer)

- Myers: From The Archives: No-Till Boosts Income While Saving Soil (July 1983 No-Till Farmer)

The 2024 No-Till History Series is supported by Calmer Corn Heads. For more historical content, including video and multimedia, visit No-TillFarmer.com/HistorySeries.